1. Add two 500g bags of whole beans to your cart

2. Add one 200g Nehi (optional roast)

3. Use the code BREWTOGETHER at checkout

The price will be automatically deducted.

The offer is valid until February 21th – or while supplies last.

Why trade models matter in the coffee industry?

Ethical coffee is all the rage now. Everyone seems to be drinking specialty coffee, sold by an ethical roastery that bought it from a small farmer in Brazil using sustainable practices. All these labels being thrown at poor consumers already got lost among these weird coffee names and origins. What does fair trade even mean anyway?! Isn’t coffee just bought from a farmer and roasted then sold in bags?

We know it’s a lot of information with no clear explanations. And because we are part of the happy bunch promoting ethical and sustainable coffee, we set out to explain in detail what the main coffee trade models are, why they matter and how our trade model is different.

The standard trade model

Let’s start with the basics: how does the standard coffee trade model work?

International trade houses, dealers, traders, and some large roasters from North America, Western Europe, or Japan buy the coffee from producing countries. This coffee is then sold to roasters via traders or specialized import agents.

In other importing countries, the model is broadly the same with small variations. In Nordic countries, trade is made directly between roasters and agents, without passing by big importers. In Eastern Europe, imports mainly come from the international trade houses based in the main coffee centers, such as Hamburg, Antwerp, or Le Havre.

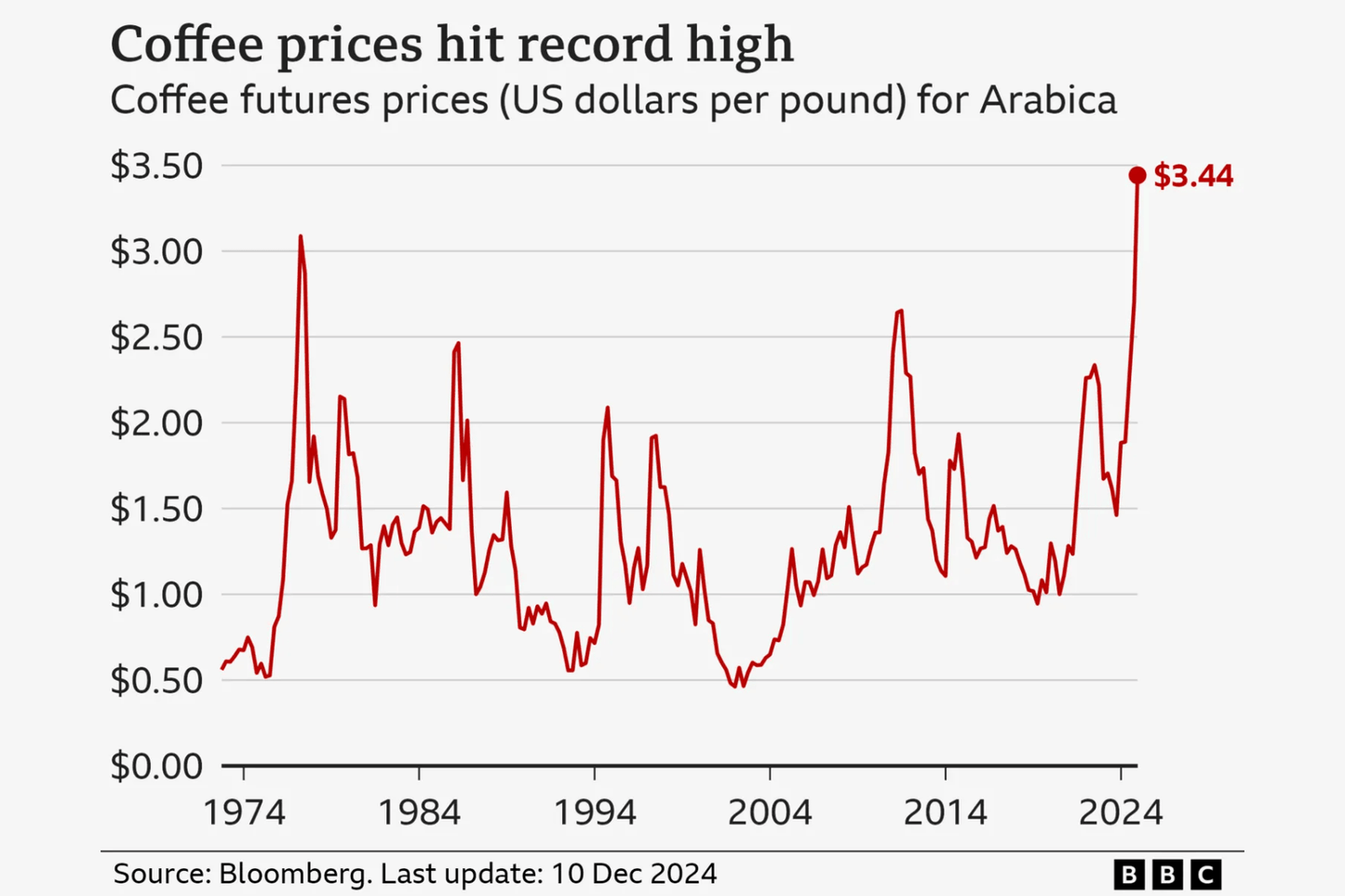

Because the coffee market is unregulated – meaning there is no minimum price set, big corporations have the power to affect prices. The world market is dominated by four multinational corporations: Kraft General Foods, Nestle, Proctor & Gamble, and Sara Lee. As they are big purchasers of coffee for their different brands, such as Maxwell House, Folgers, or Hills Brothers, the price of coffee will fluctuate depending on the quantity of beans they buy. The more coffee they buy, the higher prices will get. And inversely, if their demand is low, coffee prices will decline.

Of course, other factors can impact coffee pricing, often linked to the impact of weather on coffee production. For example, if there is a forecast of drought in Brazil, the prices will increase as it is speculated that there will be a shortage in coffee production. But in general, prices will be imposed by corporations from importing countries. In other words, by big companies from wealthy countries in North America and Western Europe – at the expense of exporters in producing countries.

In this trade model, big corporations are the winners. They can impose low prices on coffee, and coffee producers and exporters will compete against each other to have the cheapest coffee, leading to low wages in already poor producing countries. In the end, despite the promise that free trade would benefit everyone, coffee producers are the ones paying the price and barely making a living.

Fair trade models and the fair trade label organization

To counter the catastrophic consequences of the standard coffee trade, new models emerged to reduce the negative impacts on small coffee producers. The aim was to establish a new trade model that would truly benefit everyone and improve producers' living situation. This model is called fair trade: producers are paid a fair price for their coffee through a labeling system.

The fair trade model was first carried out by the Max Havelaar Foundation, created in 1988 in the Netherlands. After the label was spread to 25 countries, an umbrella organization was created in 1997: the Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International (FLO).

How does Fair trade work? The labeling organization guarantees a decent wage to producers through a set minimum price – higher than the traditional market price – and premiums as consumers pay more for their coffee. There are no middlemen who often buy from producers at low prices to sell the coffee at higher rates on the international market, thus giving these profits back directly to the producers.

To get the Fair Trade label, coffee producers must comply with the standards set by the FLO. These standards guarantee consumers that the coffee produced respects specific social, economic, and environmental criteria, such as decent wages and work conditions, no child labor, and so on.

Fair trade models seem to be a good alternative to traditional trade, but it has shortcomings. First of all, getting the certification can be challenging for small producers. They simply don’t have the money to finance all the changes they should make in their farms to meet the needed requirements. These costs are also raised as there are several certification schemes the producers need to comply with.

The second weakness is that it is consumer-led: producers only get paid if consumers buy their higher-priced coffee. As most consumers buy coffee depending on its price and many aren’t willing to pay more, the actual market size for certified coffee isn’t big. And competition is getting fiercer as more and more producers join the labeling system. Producers are likely to see a decrease in the premiums they get. Thus, this model only has a limited impact on changing the actual situation of smaller coffee producers.

The new trend: the direct trade models

As fair trade models have met increasing contestation and its limits have become more apparent, roasters have been looking for more effective and impactful trade models. That is how the direct trade model has emerged in recent years.

The term actually encompasses many different trade models, so it is generally used to refer to coffee roasters who buy straight from the farmers. Middlemen and certifications organizations such as the FLO are cut out: premiums are paid directly to the producers, and a direct relationship between roasters and producers can be fostered. The quality of the product is also higher, as roasters know precisely how the coffee is grown and harvested.

No intermediaries, direct contact with producers, higher quality coffee: these are the three characteristics that differentiate direct trade from the standard trade model. Unlike fair trade, there is no certification scheme or specific set standards. Everything relies solely on trust and transparency. This can lead to a higher impact than fair trade, as roasters can talk directly to the producers and establish together a set of rules. Usually, the general standards are sustainable production, minimum prices above fair trade, and frequent communication and visits. Direct trade models can thus be highly sustainable if both parties stand by their commitments.

But the lack of regulations can also backlash if buyers don’t pay farmers a fair wage or farmers don’t deliver the quality of coffee promised to the roasters. However, this transparency has a lot of potential if used efficiently and correctly, leaving room for a lot of improvement.

For instance, roasters can help improve farming practices by teaching farmers more eco-friendly, socially responsible practices and evaluating their product quality. Non-certified farmers can also be involved and don’t have to make huge investments to get certifications of high quality. Roasters don’t need these certifications, as they can directly assess the quality of the coffee. Direct trade could lead to more sustainable, higher quality coffee production, with fair prices for the producers.

As there is no single model for direct trade, it makes it highly adaptable to the local context and specific situations, allowing both parties to address the real, daily issues of the communities’ reality. Roasters can then share these issues with their consumers, raising their awareness on the impact they could have with a single cup of coffee.

Direct trade can thus guarantee consumers of a high-quality product traceable back to its place of origin. They can know of the production process, the farmers' living situation, know the exact value of their coffee, and why they pay a higher price.

This model can encourage sustainability in the coffee industry and create value all along the supply chain, from the producers to the consumers.

Our Impact Trade

That is why we decided to develop our Impact Trade model, taking the best of both fair and direct trade models. Our Impact Trade is at its core a direct trade model, but taken a notch further, with direct investments in local projects to have a stronger, lasting impact on the local communities. You can read more about here.

It is a direct trade model because:

- we buy directly from small farmers

- we can ensure the quality of the beans through regular visits and contact with the farmers

- we have social, economic, and environmental standards for the coffee production

- we pay fair prices above the standard price market to producers

- we build a trustful relationship with the farmers

But it’s more than that because:

- we invest a part of our profits in the local communities to empower them through project development, so our impact is bigger

- we try to give lasting solutions to root problems that will improve the producers' situations in the long term, and not only through fair wages that can only impact the short term

Our aim is to find models that won’t exploit or accentuate global inequalities, hoping that other businesses and consumers will also join the movement so that together we can build a more sustainable & ethical coffee industry that benefits coffee producers more.

Consumers can also contribute

Trade models and certifications might be a handful to understand, but they are important in changing things. Because they are at the foundation of the coffee industry and involve all the important players, they are also where the impact is the biggest. By just buying coffee from an ethical roaster with an alternative trade model, we are actually making a big difference in coffee producers' lives. Especially when all these small purchases compound in the long term, and more and more people join the movement. So the next time we stand in a supermarket, or look for a new coffee shop, let’s take a few seconds to read about where the coffee comes from and how it’s been traded before buying. It might change someone’s life, even if it’s on the other side of the planet. You can also do that now by checking our webshop and supporting the small producers who are at the heart of our Impact Trade model by buying their coffee.